Thomas Edison’s work on two other inventions, the telegraph and the telephone as a result of this the phonograph was invented. In 1877, Edison was working on a machine that would transcribe telegraphic messages through indentations on paper tape, which could later be sent over the telegraph repeatedly. This development led Edison to wonder if a telephone message could also be recorded in a similar fashion. He experimented with a diaphragm which had an embossing point and was held against quickly-moving paraffin (wax) paper. The speaking vibrations made indentations in the paper. Edison later on changed the paper to a metal cylinder with tin foil wrapped around it. The machine had two diaphragm-and-needle units, one for recording, and one for playback. When one would speak into a mouthpiece, the sound vibrations would be indented onto the cylinder by the recording needle in a vertical (or hill and dale) groove pattern. Edison gave a sketch of the machine to his mechanic, John Kreusi, to build, which Kreusi supposedly did within 30 hours. Edison instantly tested the machine by speaking the nursery rhyme into the mouthpiece, “Mary had a little lamb.” To his wonder, the machine played his words back to him.

Thomas Edison’s work on two other inventions, the telegraph and the telephone as a result of this the phonograph was invented. In 1877, Edison was working on a machine that would transcribe telegraphic messages through indentations on paper tape, which could later be sent over the telegraph repeatedly. This development led Edison to wonder if a telephone message could also be recorded in a similar fashion. He experimented with a diaphragm which had an embossing point and was held against quickly-moving paraffin (wax) paper. The speaking vibrations made indentations in the paper. Edison later on changed the paper to a metal cylinder with tin foil wrapped around it. The machine had two diaphragm-and-needle units, one for recording, and one for playback. When one would speak into a mouthpiece, the sound vibrations would be indented onto the cylinder by the recording needle in a vertical (or hill and dale) groove pattern. Edison gave a sketch of the machine to his mechanic, John Kreusi, to build, which Kreusi supposedly did within 30 hours. Edison instantly tested the machine by speaking the nursery rhyme into the mouthpiece, “Mary had a little lamb.” To his wonder, the machine played his words back to him.

It was later stated that the date for this event was on August 12, 1877, some historians believe that it most likely happened several months later, since Edison did not file for a patent until December 24, 1877. Also, the diary of one of Edison’s aides, Charles Batchelor, seems to corroborate that the phonograph was not constructed until December 4, and finished two days later. The patent (#200,521) on the phonograph was issued on February 19, 1878. The invention was highly innovative. The only other recorded evidence of such an invention was in a paper by French scientist Charles Cros, written on April 18, 1877. There were some differences, however, between the two men’s ideas, and Cros’s work remained only a theory, since he did not manufacture a working model of it.

Edison took his innovative invention to the offices of Scientific American in New York City and showed it to staff there. As the December 22, 1877, issue reported, “Mr. Thomas A. Edison recently came into this office, placed a little machine on our desk, turned a crank, and the machine inquired as to our health, asked how we liked the phonograph, informed us that it was very well, and bid us a pleasant good night.” The curiosity in the phonograph was great, and the invention was reported in several New York newspapers, and later in other American newspapers and magazines.

The Edison Speaking Phonograph Company was established on January 24, 1878, to make use of the new machine by exhibiting it. Edison received $10,000 for the manufacturing and sales rights and 20% of the profits. As a novelty, the machine was an instantaneous success, but was tricky to operate except by experts, and the tin foil would last for only a few plays.

Ever sensible and creative thinker, Edison offered the following possible potential uses for the phonograph in North American Review in June 1878:

- Letter writing and all kinds of dictation without the aid of a stenographer.

- Phonographic books, which will speak to blind people without effort on their part.

- The teaching of elocution.

- Reproduction of music.

- The “Family Record”–a registry of sayings, reminiscences, etc., by members of a family in their own voices, and of the last words of dying persons.

- Music-boxes and toys.

- Clocks that should announce in articulate speech the time for going home, going to meals, etc.

- The preservation of languages by exact reproduction of the manner of pronouncing.

- Educational purposes; such as preserving the explanations made by a teacher, so that the pupil can refer to them at any moment, and spelling or other lessons placed upon the phonograph for convenience in committing to memory.

- Connection with the telephone, so as to make that instrument an auxiliary in the transmission of permanent and invaluable records, instead of being the recipient of momentary and fleeting communication.

Over time, the newness of the invention wore off for the public, and Edison did no additional work on the phonograph for sometime, concentrating instead on inventing the incandescent light bulb.

With a void in the phonograph industry left by Edison, others moved forward to improve the phonograph. In 1880, Alexander Graham Bell won the Volta Prize of $10,000 from the French government for his invention of the telephone. Bell used his winnings to set up a laboratory to further electrical and acoustical research, working with his cousin Chichester Bell, Alexander Graham Bell, a chemical engineer, and Charles Sumner Tainter, a scientist and instrument maker. They made some improvements on Edison’s invention, primarily by using wax instead of tin foil and a floating stylus in the place of a rigid needle; this would cut into, rather than indent, the cylinder. A patent was given to Chichester Bell Charles Sumner Tainter on May 4, 1886. The machine was revealed to the public as the graphophone. Bell and Tainter had representatives approach Edison to discuss a possible partnership on the machine, but Edison refused and determined to improve the phonograph himself. At this point, he had succeeded in making the incandescent lamp and could resume his work on the phonograph. His preliminary work, though, closely followed the improvements made by Bell and Tainter, particularly in its use of wax cylinders, and was called the New Phonograph.

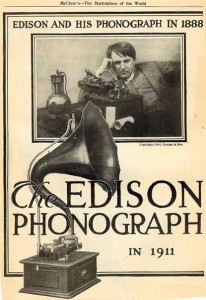

The Edison Phonograph Company was created on October 8, 1887, to market Edison’s machine. He introduced the Improved Phonograph by May of 1888, quickly followed by the Perfected Phonograph. The initial wax cylinders Edison used were white and made of ceresin, beeswax, and stearic wax.

The Edison Phonograph Company was created on October 8, 1887, to market Edison’s machine. He introduced the Improved Phonograph by May of 1888, quickly followed by the Perfected Phonograph. The initial wax cylinders Edison used were white and made of ceresin, beeswax, and stearic wax.

Businessman Jesse H. Lippincott assumed control of the phonograph companies by becoming sole licensee of the American Graphophone Company and by purchasing the Edison Phonograph Company from Edison. An arrangement which eventually included the majority of other phonograph makers as well, he created the North American Phonograph Company on July 14, 1888. Lippincott saw the possible use of the phonograph only in the business field and leased the phonographs as office dictating machines to various companies which each had its own sales territory. Regrettably, this business did not prove to be very lucrative, receiving significant resistance from stenographers.

Meanwhile, the Edison Factory produced talking dolls in 1890 for the Edison Phonograph Toy Manufacturing Co. The dolls contained tiny wax cylinders. Edison’s relationship with the company ended in March of 1891, and the dolls are very rare and sought after by many collectors today. The Edison Phonograph Works also produced musical cylinders for coin-operated phonographs which some of the secondary companies had started to use. These proto-“jukeboxes” were a development which pointed to the future of phonographs as entertainment machines.

In the fall of 1890, Lippincott became ill and lost control of the North American Phonograph Co. to Edison, who was its primary creditor. Edison changed the policy of rentals to outright sales of the machines, but changed little else.

Edison enlarged the entertainment offerings on his cylinders, which by 1892 were made of a wax known to collectors today as “brown wax.” Although they are called by this name, the cylinders could range in color from off-white to light tan to dark brown. An announcement at the beginning of the cylinder would usually indicate the title, artist, and company.

In 1894, Edison declared bankruptcy for the North American Phonograph Company; this enabled him to buy back the rights to his invention. It took two years for the bankruptcy to be settled before Edison could move ahead with marketing his invention. The Edison Spring Motor Phonograph appeared in 1895, even though technically Edison was not permitted to sell phonographs at this time because of the bankruptcy agreement. In January 1896, he started the National Phonograph Company which would produce phonographs for home entertainment use. Within three years, branches of the company were located in Europe. Under the sponsorship of the company, he announced the Spring Motor Phonograph in 1896, followed by the Edison Home Phonograph, and he began the commercial issue of cylinders under the new company’s label. A year later, the Edison Standard Phonograph was produced, and then exhibited in the press in 1898. This was the first phonograph to bear the Edison trademark design. Prices for the phonographs had considerably diminished from its early days of $150 (in 1891) down to $20 for the Standard model and $7.50 for a model known as the Gem, introduced in 1899.

Standard-sized cylinders, which tended to be 4.25″ long and 2.1875″ in diameter, were 50 cents each and typically played at 120 r.p.m. A assortment of selections were featured on the cylinders, including marches, sentimental ballads, coon songs, hymns, comic monologues and descriptive specialties, which offered sound reenactments of events.

The early cylinders had two major problems. The first was the short length of the cylinders, only 2 minutes. This essentially narrowed the field of what could be recorded. The second problem was no mass method of duplicating cylinders existed. Most often, performers had to repeat their performances when recording in order to accumulate a quantity of cylinders. This was not only time-consuming, but costly.

The Edison Concert Phonograph was revealed in 1899, retailing for $125, which had a louder sound and a larger cylinder measuring 4.25″ long and 5″ in diameter, the large cylinders cost $4. The Concert Phonograph did not sell well, and prices for it and its cylinders were significantly reduced. The production of the Concert Phonograph ceased in 1912.

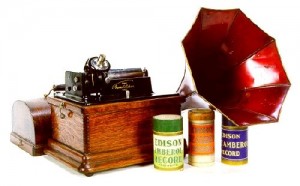

The ability to mass-produce duplicate wax cylinders was put into effect in 1901. The cylinders were molded, rather than engraved by a stylus, a harder wax was used. The process was referred to as Gold Molded, because of a gold vapor given off by gold electrodes used in the process. Sub-masters were produced from the gold master, and the cylinders were made from these molds. From a single mold, 120 to 150 cylinders could be produced every day. The new wax was black in color, and the cylinders were originally called New High Speed Hard Wax Molded Records until the name was changed to Gold Molded. By mid-1904, the savings in mass duplication was reflected in the price for cylinders which had been lowered to 35 cents each. Beveled ends were made on the cylinders to accommodate titles.

A new business phonograph was introduced in 1905. Similar to a standard phonograph, the reproducer and mandrels were altered. These early machines were difficult to use, and their delicateness made them prone to failure. Even though improvements were made to the machine over the years, they cost was still more than the popular, inexpensive Dictaphones produced by Columbia. Electric motors and controls were added afterwards to the Edison business machine; these additions improved the performance of the business phonograph. Some Edison phonographs that were made before 1895 had electric motors, until they were replaced by spring motors.

The Edison business phonograph became a dictating system. Three machines were used: the executive dictating machine, the secretarial machine for transcribing, and a shaving machine used to recycle used cylinders. This system can be seen in the Edison advertising film, The Stenographer’s Friend, filmed in 1910. The Ediphone was an enhanced version of this machine that was introduced in 1916 and increasingly grew in sales after World War I and into the 1920’s.

The 2-minute wax cylinder could not compete well beside the competitors’ disc records, which could offer up to four minutes of play time. In response, the Amberol Record was offered in November 1908, which had finer grooves than the two-minute cylinders, and thus, could last as long as 4 minutes. The two-minute cylinders became known as the Edison Two-Minute Records, and then afterwards were known as the Edison Standard Records. In 1909, a series of Grand Opera Amberols (a continuation of the two-minute Grand Opera Cylinders introduced in 1906) was introduced to attract the affluent patrons, but these did not prove successful. The Amberola I phonograph was introduced in 1909, a floor-model luxury machine with high-quality performance. This was supposed to compete with the Victrola and Grafonola.

In 1910, the company was reorganized into Thomas A. Edison, Inc. Frank L. Dyer was originally president, then Edison served as president from December 1912 until August 1926, when his son, Charles, became president, and Edison became chairman of the board.

Columbia, one of Edison’s major competitors, abandoned the cylinder market in 1912. (Columbia gave up making its own cylinders in 1909. From 1909 to 1912 Columbia was only releasing cylinders which it had acquired from the Indestructible Phonographic Record Co.) The United States Phonograph Co. ceased production of its U.S. Everlasting cylinders in 1913. This left the cylinder market to Edison. The disc had progressively grown in popularity with the consumer, due to the popular roster of Victor artists on disc. Edison refused to give up the cylinder, introducing the Blue Amberol Record. This was an unbreakable cylinder with what was debatably the best available sound on a recording at the time. The finer sound of the cylinder was partly due to the fact a cylinder had constant surface speed from beginning to end. This was in contrast to the inner groove distortion that occurred on discs when the surface speed slowed. Supporters of Edison also argued that the vertical cut in the groove produced a superior sound to the lateral cut of Victor and other disc competitors. Cylinders had truly peaked by this time, and even the superior sound of the Blue Amberols could not persuade the larger public to buy cylinders. Edison conceded to this reality in 1913 when he announced the manufacture of the Edison Disc Phonograph.

Nice writing style. Looking forward to reading more from you.

Chris Moran

I learned some great facts from this article about Edison and the phonograph.

wow! Nice detailed post on the History of the Edison Cylinder Phonograph.

Very informative article. Lots of great information.

Really nice information. Want to read more in the future.

Gotta love the effort you put into this blog 🙂

Hi

I own an Eddison Phonograph and approx 25 was cylinders just wondering what its value would be today

regard

Denise Evans

The Linen co UK

The phonograph is very efficiant